The University of Music and the Mendelssohn Family

At the heart of the early plans for a Berlin Conservatory was Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy—not at the inception of its actual founding, but rather at the beginning of an attempt that ultimately petered out. When King Friedrich Wilhelm IV ascended the throne in 1840, marking a generational dynastic change, new hopes emerged. The new monarch negotiated with Mendelssohn, who had grown up in Berlin but was at the time directing the Gewandhaus concerts in Leipzig. In the end, Mendelssohn turned his back on Berlin, and in 1843, a conservatory was founded—not by the Spree River but by the Pleisse River—inspired by the Paris Conservatoire. This institution would go on to exert a major influence in the decades that followed. Mendelssohn refused to become a “conservatory schoolmaster” in the Prussian capital, choosing instead to focus on his “good, fresh orchestra.” He expressed his frustrations with “the Berlin hybrid”: “grand plans, tiny execution; perfect criticism, mediocre musicians; liberal ideas, court servants on the streets […] and the sand.”

It would take almost three more decades before Prussia’s state conservatory finally came into being in the autumn of 1869. During the intervening years, the failed revolution of 1848 had taken place, during which the founding of a music school for the capital was a major topic of discussion among the bourgeoisie. In 1850, Julius Stern—a singing teacher and conductor supported by Giacomo Meyerbeer—opened a private music school alongside Adolph Bernhard Marx and Adolf Kullak. This institution would later become the Stern Conservatory. However, as if to compensate for the initial misstep, the founder of the Berlin Hochschule was a former protégé of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: Joseph Joachim. In 1844, while still a teenager, Joachim had performed Beethoven’s Violin Concerto in London to great acclaim under Mendelssohn’s baton. Joachim and the Hochschule maintained many ties with the Mendelssohn family, not least with the Mendelssohn Bank. Joachim also succeeded in laying the groundwork for the Mendelssohn Foundation in honor of the composer.

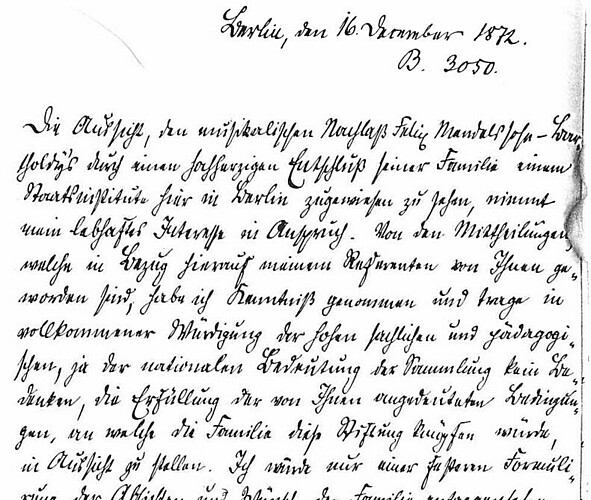

To promote the fledgling Hochschule and preserve Mendelssohn’s legacy in Berlin, Joachim worked to ensure that Mendelssohn’s estate—the “remaining manuscripts”—was transferred to the Royal Library in Berlin. The Kensington Museum in London had also expressed interest in purchasing them. It was Joachim’s idea to establish a state scholarship for young musicians in exchange. This project was initiated as early as 1872, as evidenced by documents preserved in the archive of the Berlin University of the Arts. While the foundation's charter was not finalized until 1878, the arrangement was successful. Joachim ensured that the Berlin Hochschule received certain advantages: applicants were required to be “students of state-subsidized music education institutions in Germany.” The scholarship was awarded by a three-member board of trustees, chaired by the “current director of the Hochschule für Musik in Berlin,” which was initially Joseph Joachim himself.

Starting in 1879, scholarships were awarded for composition and “performance art,” along with grants. The first recipient, in 1879, was Engelbert Humperdinck. Early female recipients included violinists Marie Soldat (1880) and Joachim’s student Gabriele Wietrowetz (1883). A look at the extensive list of awardees, compiled by Rudolf Elvers, former head of the music department at the Berlin State Library, reveals many notable figures in Berlin’s music and music education history, as well as individuals who achieved prominence far beyond Berlin. A few randomly selected names include: Philipp Wolfrum and Ethel Smyth (1881), Waldemar von Baußnern (1887), Bram Eldering (1890), Paul Juon (1896), Frieda Hodapp (1897/98), Karl Klingler (1900), Otto Klemperer (1906, honorable mention), Licco Amar (1912), Wilhelm Kempff (1915 and 1917), Kurt Weill (1919), Erwin Bodky (1920), Berthold Goldschmidt and Max Rostal (1925), Ignace Strasfogel (1926), Grete von Zieritz (1928), Roman Totenberg (1931), as well as Norbert von Hannenheim and Harald Genzmer (1932). In the year the Nazis seized power, 1933, one recipient was Karlrobert Kreiten, who was later executed in 1943 for making defeatist remarks against the Nazi regime. Among the 1882 laureates was also a family member: composer Arnold Mendelssohn, a great-grandson of Moses Mendelssohn, who had studied at the Berlin Institute for Church Music.

The Nazis unlawfully removed Mendelssohn’s name from the scholarship, renaming it the “Prussian State Scholarship for Musicians.” Nonetheless, the funds of an additional foundation remained untouched under the Hochschule für Musik’s administration throughout the twelve years of the Nazi regime. The scholarship was re-established in 1963. It is now administered by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, and its historical connection to the Prussian-German capital is reflected in the fact that the award ceremony continues to take place in Berlin. The participant pool still includes students from all German music universities.

The Mendelssohn family’s patronage of the Berlin Hochschule für Musik extended beyond the Mendelssohn Prize. The Mendelssohn Bank repeatedly supported the institution, for instance, by providing financial backing for the Joseph Joachim Foundation. This was one of many foundations established during the late Kaiser era, but it did not survive the inflationary period after World War I and the monetary collapse of 1923.

For the new university building on Fasanenstraße, inaugurated in 1902, the Mendelssohn Bank provided funds for decorating the vestibule in the teaching wing with figurative stained-glass windows. The artist Melchior Lechter, a book illustrator associated with the circle of poet Stefan George, was commissioned to create the designs, which are preserved in his estate at the Landesmuseum Münster. However, Kaiser Wilhelm II, who famously considered himself an authority on the visual arts, disapproved of the Jugendstil-style figures and color scheme and intervened personally to halt the project. Joseph Joachim stubbornly refused to touch the substantial sum earmarked for the project, leaving it untouched for the rest of his life.

The Mendelssohn family was also involved in the association that established a Joachim monument in the Old Concert Hall, which no longer exists due to war damage. The monument, created by Adolf von Hildebrand, was unveiled in 1913 but was quietly dismantled by the Nazis.

Finally, there were personal connections between the Mendelssohn family and the Hochschule für Musik, both among its faculty and students. For instance, the first viola professor, Emil Bohnke, who was also a composer and conductor, was married to Lilli Mendelssohn, a student at the institute. Tragically, both died in a car accident in 1928 on their way to the Baltic Sea. In response, the Mendelssohn family established the Emil Bohnke Foundation through a donation to the Hochschule.

Author: Dr. Dietmar Schenk, former head of the University Archive