Joseph Joachim

Joseph Joachim

When the centenary of Joseph Joachim’s death was commemorated in 2007, David Schoenbaum, the social historian of the violin, titled his article in the New York Times, “Another Ovation for Joachim (Who?)”. Schoenbaum’s implication is relevant here as well: Joseph Joachim achieved fame and honor far beyond the German-speaking world during his lifetime, followed by a legacy as a significant and successful musician, although his renown was later interrupted by the Nazi regime. Today, at the Berlin University of the Arts, we encounter Joachim daily: the concert hall at the Bundesallee campus is named after him, and both a bust and a marble statue in the Fasanenstraße campus commemorate his legacy. Yet it’s likely that many who pass through these halls have only a vague notion of his personality and achievements.

This lack of familiarity can be attributed, in part, to the period he lived in and the history of recording technology. We are familiar with the works of his friend, Johannes Brahms, a composer, because they continue to be performed, and we can listen to recordings by later generations of violinists, as these were made possible by the advent of reproducible sound. But only a few recordings of Joachim himself survive from his later years—such as the Bourrée from Bach’s Partita No. 1 in B Minor and the first two Hungarian Dances by Brahms—offering only glimpses of Joachim’s violin artistry.

However, here we are particularly interested in another aspect of his legacy: Joachim directed the Berlin University of Music for almost forty years, from 1869 to 1907, training hundreds of violinists and a few female violinists alongside his colleagues. When classes began in September 1869, there were just 19 “pupils”—male and female—enrolled. By the time of his death, Joachim was heading an institution that had, five years earlier, moved into a grand new building in Charlottenburg, at the corner of Hardenberg and Fasanenstraße. From a modest “School for the Practice of Music,” it evolved into the Royal Academic University of Music, one of Germany’s leading conservatories during the prosperous Kaiserzeit.

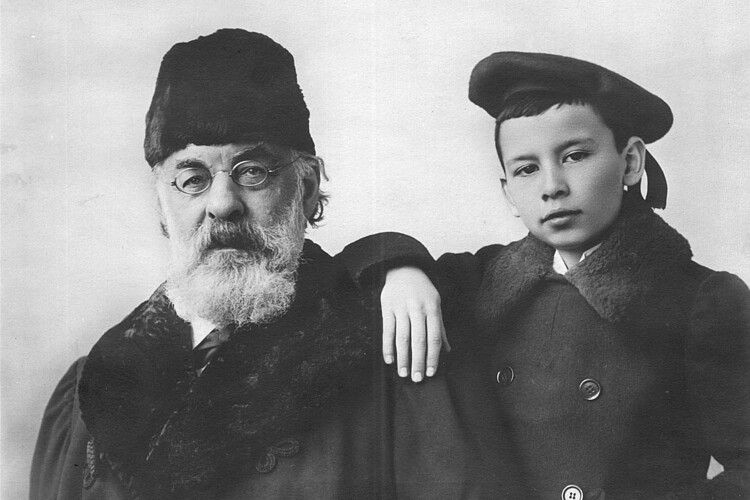

Joseph Joachim was born on June 28, 1831, in Kittsee (known in Slovak as Kopčany, and in Hungarian as Köpcsény) in Burgenland, then part of Hungary, the seventh child of a Jewish merchant. He first performed publicly in the noblemen’s casino in Pest, now Budapest, in 1839. This early debut was later commemorated with elaborate celebrations in Berlin for the 50th and 60th anniversaries of his artistic career in 1889 and 1899. Recognizing his musical talent, Joachim was sent to Vienna to study under Joseph Böhm. In 1843, he moved to Leipzig, where he was mentored by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Just a year later, he earned accolades in London for his interpretation of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. By 1850, Joachim was concertmaster in Weimar, joining the circle around Franz Liszt. After relocating to Hanover in 1853, he met Robert and Clara Schumann, as well as Brahms, forging strong bonds with them while distancing himself from the “New German School.” He converted to Lutheranism and married the singer Amalie Schneeweiß from Graz.

After the downfall of the Welf court during the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, Joachim moved to Berlin. In 1869, the Prussian government tasked him with founding a music school. Following the Leipzig model, the Berlin University of Music, Prussia’s conservatory, was established, with Joachim stepping into a role similar to Mendelssohn’s. That same year, Richard Wagner republished his antisemitic essay, Judaism in Music, lamenting, with a reference to Joachim, the “defection” of a “great violin virtuoso.”

The early years of the Berlin University of Music also saw Joachim embroiled in a heated dispute with the Prussian Minister of Culture, representing the authoritarian state. This clash occurred in the midst of the Franco-Prussian War, as Joachim aligned himself with the national-liberal movement. The King, from the German military headquarters in Versailles, rejected Joachim’s offer to resign but did yield on some points, leading to Joachim’s treatment with greater deference. He was increasingly seen as a steward of the arts and, specifically, a guardian of the “great masters” like Bach and Beethoven—one whom the Prussian state approached with respect.

Today, Joachim’s enduring influence can be traced through a remarkable collection of ornately crafted certificates, awards, and acknowledgments in the University Archive, a gift from his children to the University in 1931, along with documents related to the school’s founding. What remains is Joachim’s ideal of faithful interpretation, distinguishing him from a virtuoso like Paganini, as he devoted himself to the authentic rendition of musical works.