Wanda Landowska

Wanda Landowska

Women were already employed as teachers at the Berlin University of Music during the imperial era. The “lady with the harpsichord”, Wanda Landowska (1879-1959), had a particularly high reputation. From the turn of the century, she dedicated herself to the “renaissance of the harpsichord” from Paris and taught in Fasanenstraße from 1913 to 1919. Her “experimental” harpsichord class was considered a novelty at the time.

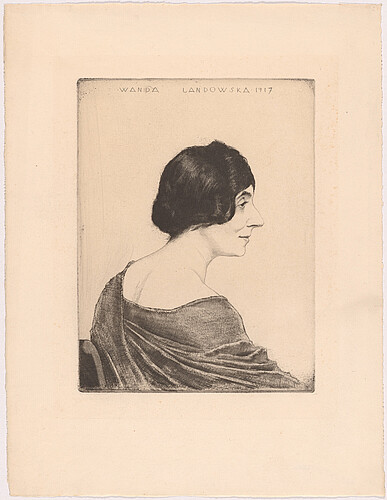

A portrait of the harpsichordist Wanda Landowska was published in 1924 in the widely read bi-monthly magazine Die Musik. The author Richard Stein looks back exactly a decade, to the days before the outbreak of the 'Great War', when a congress of the International Music Society was taking place in Paris. It was there that he last met Landowska. “We were coming from the Palace of Versailles, where a historic concert had taken place in the Hall of Mirrors,” he recalls. The “aged Saint-Saëns” and Gabriele d'Annunzio, the Italian writer, were among the visitors. He describes Wanda Landowska as “a delicate, inconspicuous figure in unadorned garb”. “Slowly, almost humbly, with gliding steps and, as always, leaning slightly forward”, she stepped onto the podium; ‘she [...] did not hear the applause that greeted her from all sides’. And “when the performance was over, the strange thing happened that Saint-Saëns [...] rushed up to the artist and kissed her hand with obvious emotion”.

At the time of this triumph in Paris, Wanda Landowska was already working in the Prussian-German capital: at the Berlin University of Music. Hermann Kretzschmar, the director, also held the chairmanship of the International Music Society for a time, in addition to many other offices and posts; Landowska had been appointed on his initiative the year before her aforementioned performance. According to Landowska, the Berlin University had anticipated similar efforts in St. Petersburg and Paris by establishing a harpsichord class.

On May 24, 1914, Landowska presented her mission to a wider Berlin public in the Vossische Zeitung. The “Renaissance of the Harpsichord” is the title of her manifesto. The “harpsichord question” was now being “taken seriously”, she wrote. To a certain extent, she foresaw the development of early music that had occurred in the meantime: “Sooner or later, we will see the founding of museums where we will get to know the originals” - she means the music of the 17th and 18th centuries - “in their pure, original form.” The treatise Musique Ancienne, which Landowska had written together with her husband Henri Lew-Landowski, had been available since 1909; it was published in Paris, where the couple lived at the time. The library of the University of the Arts owns a copy given to her personally by the artist; it contains a handwritten dedication, written in purple ink, which she liked to use.

Wanda Landowska was born in Warsaw in 1879. She came from an art-loving, educated Jewish family; her father was a lawyer and her mother worked as a translator from English. She attended the conservatory in her hometown and moved to Berlin at the age of 17, where she studied piano with Moritz Moszkowski and composition with Heinrich Urban. Early on, she was fascinated by early music, especially Johann Sebastian Bach. By 1904, she was already so well known that she was able to visit the collection of early musical instruments at the Berlin University of Music in the presence of its director, Oskar Fleischer, as a guest from Paris. Henri Lew, who accompanied his wife, wrote to Paris that a concert by Landowska was imminent; “only the teaching staff of the Royal Academy and the court as well as other celebrities” had been invited.

Landowska lived in Paris from 1900 to 1913, where she taught at the Schola Cantorum. During the Bach Days in Breslau in 1912, she presented a harpsichord built by Pleyel, which she was to use in the rest of her concert career. Hermann Kretzschmar, a kind of “music pope” in Berlin, was in correspondence with Landowska. It is striking that he arranged several appointments of people who were influenced by French culture, including the violinist Henri Marteau. After Landowska's appointment, Kretzschmar procured a Pleyel harpsichord especially for the university.

With an annual salary of 4,000 Mark, Landowska taught up to 12 hours a week according to her employment contract. The salary corresponded to that of a “regular teacher”. The number of her students remained small - perhaps also due to the war - but among them were Alice Ehlers and Anna Linde, two people who made records in the 1920s. Ehlers performed with the two Hindemith brothers at the university in 1927 on the occasion of Paul Hindemith's appointment. Hindemith played viola d'amore, his brother Rudolf a bass viol and Alice Ehlers harpsichord.

Landowska's stay in Berlin was overshadowed by the First World War, which began in the summer of 1914. She now found herself in the firing line of angry nationalists, as she was, formally speaking, a Russian citizen. In her favor, however, it could be argued that she was a “must-Russian”: Björnstjerne Björnsen, the Norwegian writer and inspirer of naturalism, who enjoyed a high reputation in Germany, publicly defended Landowska. At the time, Poland was part of the Tsarist Empire and Landowska felt Polish. It is said that her apartment at Sächsische Straße 6, Wilmersdorf, resembled a Chopin museum. Souvenirs of her visit to Tolstoy in Jasnaja Poljana (winter 1907/08) were also on display there.

In the days of the revolution in Berlin, which led to the proclamation of the republic on November 9, 1918 and resulted in civil war-like unrest, she then had to defend herself against another accusation: She was now rumored to be a sympathizer of Bolshevism. In February 1919, the Berlin press complained under the headline “The Spartacist Orchestra” that the Blüthner Orchestra had performed at a funeral service in honor of the murdered Rosa Luxemburg. The “financial backers” were to be found in Polish-Russian circles “grouped around Mr. Landowski and his wife, the well-known harpsichordist and teacher at the Prussian Academy of Music, Wanda Landowska.” Landowska sent a laconic denial: “Mrs. Landowska only deals [...] with the music of the 18th century”. The worst thing, however, was that her husband and mentor Henri Lew died under unexplained circumstances.

The harpsichord lessons, which were introduced on a trial basis, lost support 'from above' after the political upheaval. Kretzschmar, still director of the university, agreed in a report to his superior authority, the Prussian Ministry of Culture, that the experiment should be discontinued in July 1919. This had been preceded by a contact with the “this side's advisor”, who was probably Leo Kestenberg, who had just taken up his post at the ministry. Wanda Landowska left Berlin, which had brought her no luck, and went to Paris via Basel. In the 1920s, there was no longer a harpsichord class at the university.

Wanda Landowska was now back in Paris. In 1925, she opened an Ecole de Musique Ancienne in St.-Leu-La-Forêt, not far from the city, where she held courses and gave concerts. Manuel de Falla dedicated his harpsichord concerto to her in 1926, and shortly afterwards Francis Poulenc wrote the Concert champêtre for her. After the occupation of France by the German Reich, Landowska and her assistant Denise Restout managed to obtain a visa for the USA in 1941. She settled in Lakeville, Connecticut, and was able to continue her impressive career.

Harpsichord lessons were only resumed at the Berlin Hochschule after the National Socialist takeover. Eta Harich-Schneider, a student of Landowska's, was employed. In 1934, during the “Third Reich”, she invited her teacher to a course in her private apartment on Kurfürstendamm, which required a certain amount of courage. However, she makes no mention of this in her book Die Kunst des Cembalo-Spiels (“The Art of playin Cembalo”) (1939); Landowska rightly found this annoying.

Two decades later, Landowska's teaching activities had a bureaucratic aftermath, as can be seen from the university files, which shows how intensively the National Socialists tracked down Jewish people: In 1937, the Reichsmusikkammer and in 1941 the Reichsstelle für Sippenforschung made enquiries. As the Dutch researcher Willem de Vries was able to uncover, their valuable collection of instruments fell victim to Nazi art theft after the occupation of France by the German Reich: in 1940, the “Sonderstab Musik” (special music staff) in the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg confiscated their extensive possessions and brought them to Berlin.

After these events came to light, the composer Walter Zimmermann, who teaches at the University of the Arts, created the work Wanda Landowska's vanished instruments for midiharpsichord, fortepiano and computer projections (1998/99).

Author: Dr. Dietmar Schenk, former Director of the University Archives